Constructing the Edition

What is a Critical Edition?

There were no printing presses in the Middle Ages; whenever someone needed a new copy of a book, a scribe had to copy it out by hand. Every copy of the book was different, because scribes made mistakes or deliberately added or removed text. Original manuscripts rarely survive; for most works, we have only the corrupt copies.

Modern scholars who study medieval works need to have access to the texts, but they cannot just borrow an eight-hundred year-old manuscript from the local library. Often they must travel to distant countries and get special permission to examine manuscripts. And, since each copy of the work is different, historians can never be sure how close the text they are reading is to what the medieval author intended.

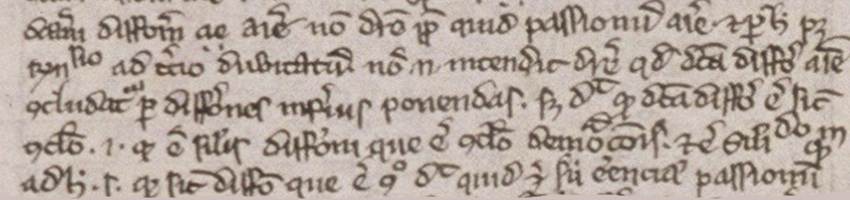

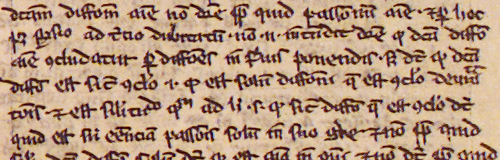

Finally, you can see from the three examples shown here that the words are abbreviated, the punctuation is irregular, the writing is tiny, and the handwriting is difficult to read. Few people can read medieval manuscripts readily, even after they have had a course in paleography -- the study of old handwriting.

These samples reproduce the same passage in three different manuscripts. If you look closely, you can see that the wording is not exactly the same.

Paleographers who know the medieval literature make texts that survive only in manuscript available seek to reconstruct the original that was copied differently by different scribes. They judge what words belong to the text and what words are mistakes, by careful attention to context and sense and weighing the value of the manuscript witnesses that preserve each possible reading. A critical edition presents both the reconstructed text and an apparatus of variant readings that enables readers to second guess the editor and chose a rejected reading. A second apparatus supplies the footnotes omitted by medieval authors, notes explaining techical terms, parallel passages from contemporary authors, etc.

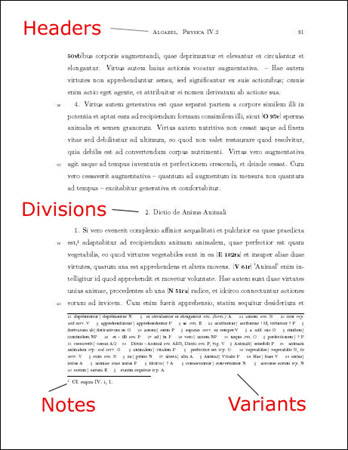

The example below shows a page from a critical edition. Directly below the main text that the editors have established, you can see the rejected variants readings. Scholarly notes appear at the bottom of the page. Major divisions in the text such as book numbers come from the original work, other minor divisions are numbered by the editor to facilitate reference. Line numbers are added so that readers can match the variants with the text. Other modern conventions include page headers, which are also intended to help readers find their place.

How We Work

The Rufus Project is producing critical editions of Richard Rufus of Cornwall's surviving works. Hard at work on the project is a team of editors from around the world, experts on medieval logic, Latin, philosophy, Rufus' contemporaries, Aristotle, and typesetting. The following are the steps involved in producing a critical edition of one of Rufus' works.

1. The first step is to find and describe manuscripts containing works by Rufus. We travel to libraries in Erfurt, Florence, Madrid, Rome, Oxford, Paris, and Prague to describe manuscripts in which works by Rufus may be found.

2. Before we travel we obtain microfilm copies of the manuscripts in which we are interested. For all the major manuscripts, we try to get computer-readable images in TIFF format which offers the best protection against loss of information. We then use sophisticated computer software to enhance the images, making them easier to read.

3. Next, we transcribe the work, noting ambiguous abbreviations, odd letter forms, and problems with the logical coherence of the text. We read through each manuscript, carefully two or three times checking its readings against the other copies. We keep records of the obvious errors in each manuscripts -- places where the scribe's eye has skipped from a word on one line to a similar word on another line. On the basis of this information and dating information about the manuscripts, we determine what manuscripts should be given greatest weight in determining the text.

The process of comparing the manuscripts to one another is called “collation.” One person reads the manuscript aloud while a second person records its variants against the initial transcription, either on a paper copy or directly into the file on computer.

4. Once all the manuscripts have been read, one of us reads carefully though the text, establishes a preliminary text, and verifies the obvious references. The preliminary text is read critically by several editors. We sit down together and work collaboratively to "establish the text," a process intended to reconstruct a text as closely as possible to the original.

5. Also at this time, we prepare a set of notes based on the work we have done on Rufus' predecessors, his contemporaries, and references to Rufus' views by later authors. These notes help us establish the text, and they are also useful to readers.

When the text is established, we begin writing an introduction to the text that describes manuscripts and that deals with questions of authenticity and dating. It also introduces some of Rufus' more important views.

When we have problems with our text -- places where we cannot understand what is being said -- we refer to other specialists. Specialists from Hamburg, Los Angeles, Montreal, New Haven, Palo Alto, and Paris join us to talk through the hardest problems with the provisional edition.

6. We read the manuscripts once more prior to typesetting to make sure the readings are as accurate as possible.

7. Lastly, we typeset the entire work and redact the indices -- subject index, author index, and manuscript index -- and, of course, read through the text once again.